Blog

The economic cost of Indonesia’s sugarcane industry

The archipelago nation of Indonesia has a long history of promoting food self-sufficiency.

The nation’s first President (1945-1967) famously stated:

Why bother talking about political freedom if we don’t have freedom to manage our rice?

As an example of the importance of food self-sufficiency to the country, the current Indonesian President (2025- ) has sponsored a roadmap to food and energy self-sufficiency. A resurgence in Indonesian protectionist trade policies is situated within a wider trend of falling merchandized trade as a percentage of GDP since the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98 (Patunru, 2018). While the same metric shows real increases in other large Asian economies: Vietnam, India and China.

Sugar plays an important role in Indonesia’s agricultural profile. In the 10-years to 2020, sugar consumption in Indonesia grew 40%. Global consumptions grew at 9% over the same period. Indonesia is the world’s second largest importer of sugar. The U.S. Department of Agriculture predicts that Indonesia will import 5.1 million tonnes of sugar in 2025-26. There is currently a significant mis-match between the political rhetoric of food self-sufficiency, domestic demand, and economic well-being of Indonesian households.

Indonesian sugar farm production is relatively low. In 2023, tonnes per hectare was estimated at 69. In 1961, Indonesia’s farm production was estimated at 137, approximately double. Indonesia’s average farm production per hectare is at world average, but below neighboring countries Australia (99 tonnes), India (83) and China (80).

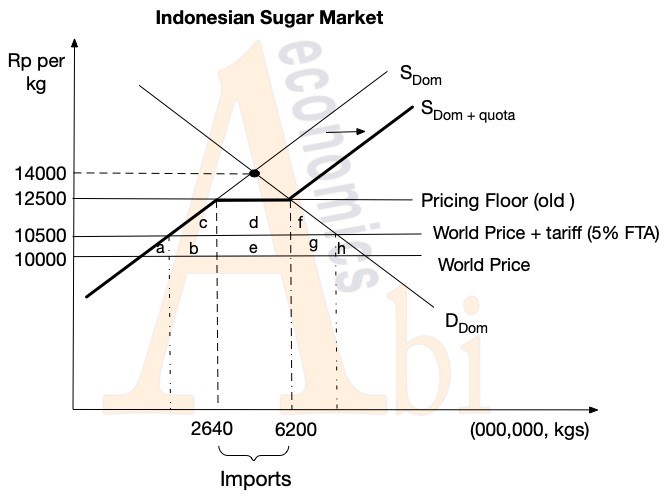

A report in the English language newspaper – The Jakarta Post – asserted that Indonesia imported 3.56 million tonnes of sugar in 2024-25[1]. This on-top of 2.64 million tonnes of domestic production. Figure 1 depicts a range of trade protection measures employed by Indonesia: 5 percent tariff (see Unit 4.1, Chapter 20), a price floor (Unit 2.1, Chapter 6) and a quota system (Unit 4.1, Chapter 20).

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated that that Indonesia imported 5.2 million tonnes over the same period, equal with China.

Figure 1: Indonesian trade and trade protection model of sugar in 2024.

Relative to a free-trade environment of no trade protection barriers, imported sugar would be available at approximately Indonesian rupiah 10,000 per kg (or US$0.62 per kg). Rather Indonesia sets a minimum price of 12,500 per kg[1]. This higher minimum price induces efficiency losses of areas “a + b + c” and “f + g + h”. The areas “a + b + c” represent production inefficiencies of increased domestic production above the low-cost imports. The areas “f + g + h” represent efficiency losses due to the need to ration consumer demand reduced total sugar supply.

[1] Recently raised to 14,000 for a fixed period of time.

The combination of restricting low-cost imports and surging domestic demand has forced the Indonesian government to apply further market interventions. With each intervention bringing an added layer of resource allocation inefficiencies. The policy to protect relatively high-cost domestic sugar production, in the face of surging domestic demand, has seemingly forced the government to cap domestic prices. Irvan Maulana (2025) summarizes the consequences:

Recently raised to 14,000 for a fixed period of time.

“Government-imposed low sugar prices intended to protect consumers and industry actually harm farmers. The reference price fails to cover production costs, pushing farmers to switch to more profitable crops. Supply to mills has plummeted, with up to 70 percent of farmers affected. Mills, in turn, cannot invest or upgrade due to falling supply”.

Government interventions ‘supporting’ domestic farmers and consumers are working against one another. Capping prices below the market equilibrium provides a disincentive for domestic farmers to remain in the sugar industry. A substitution to other crops limits supply and revenue to sugar Mills. Sugar mill technology is important as it determines, among other things, whether sugar cane can be processed green or whether it must be burnt prior to processing, in order to dry it. A lack of investment results in a less internationally competitive domestic industry.

Despite the rhetoric, Indonesia’s current food self-sufficiency policies are reducing the economic well-being of citizens. A continuation of the combined policies of price floors well above the international price and weak supply-side institutional structure, will likely contribute to a reduction in long-term financial security for relatively poor households. While multilateral trade initiatives may be current dead, Indonesia risks not being able to more rapidly lift many of its poor out of poverty due to popularist policies that appeal to notions of nationalism. The following continues to have resonance for Indonesia, despite the change international trade environment now, compared to pre-Covid 2018 quote. “Globalization can have both positive and negative results, but Indonesia has to continue its reforms in order to make the most out of its engagement with the rest of the world….At the same time, it is important to increase Indonesia’s engagement with the international architecture as it would help to reduce trade barriers, provide policy discipline to withstand rent-seeking activities, and frame policy reform” (Patunru, 2018).

References

Czapp, (2022). How High can Indonesian sugar consumption go? Chini mundi. (11.01.2022).

https://www.chinimandi.com/how–high–can–indonesian–sugar–consumption–go/

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2025) – with major processing by Our World in Data.

“Sugar cane yields – UN FAO” [dataset]. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Production:

Crops and livestock products” [original data]. Retrieved August 16, 2025 from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250731–180103/grapher/sugar–cane–yields.html (archived on July 31, 2025).

Maulana, I (2025). The bitter reality behind sugarcane downstreaming. The Jakarta Post (04.08.2025).

https://www.thejakartapost.com/opinion/2025/08/04/the–bitter–reality–behind–sugarcanedownstreaming.html

Patunra, A (2018). Rising Economic Nationalism in Indonesia. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, Vol 35(1).

pp 335-354. https://berkas.dpr.go.id/perpustakaan/sipinter/files/sipinter—087–20200728155912.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture (2025). Sugar: World Markets and Trends. Foreign Agricultural Service. (May, 2025). https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/sugar.pdf